*Interview taken from: http://www.foyles.co.uk/Author-Bandi

Questions & Answers

About The Author

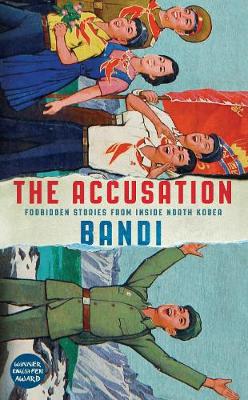

Bandi is the Korean word for firefly. It is the pseudonym of an anonymous dissident writer still living in North Korea. In 1989, Bandi began to write a series of stories about life under Kim Il-sung's totalitarian regime. The Accusation provides a unique and shocking window on this most secretive of countries. Bandi's profound, deeply moving, vividly characterised stories tell of ordinary men and women facing the terrible absurdity of daily life in North Korea: a factory supervisor caught between loyalty to an old friend and loyalty to the Party; a woman struggling to feed her husband through the great famine; the staunch Party man whose actor son reveals to him the absurd theatre of their reality; the mother raising her child in a world where the all-pervasive propaganda is the very stuff of childhood nightmare. The Accusation is a heartbreaking portrayal of the realities of life in North Korea. It is also a reminder that humanity can sustain hope even in the most desperate of circumstances - and that the courage of free thought has a power far beyond those seek to suppress it.

Bandi's translator is Deborah Smith, whose other translations from Korean include two novels by Han Kang, The Vegetarian and Human Acts, and two by Bae Suah, A Greater Music and Recitation. In 2015 Deborah completed a PhD at SOAS on contemporary Korean literature and founded Tilted Axis Press. In 2016 she won the Arts Foundation Award for Literary Translation. She tweets as @londonkoreanist.

Below, exclusively for Foyles, we talked to Deborah about the characteristics of North Korean fiction, and the urgent, oral quality of Bandi's writing, how and why she became a translator of Korean literature and why she is feeling encouraged by the current state of ficiton in translation in the UK.

What do we know about Bandi?

Well, ‘Bandi’ is a pseudonym - it means ‘firefly’. According to the book’s afterword, he is a member of North Korea’s state-authorised Writers’ League, and wrote these stories - which must be very different from the official work he’s able to produce - in secret. They were smuggled out of the country, but he himself has remained behind, so I imagine other details of his biography must have been changed to protect his identity.

Can you describe for our readers what picture The Accusation paints of life in North Korea?

Firstly, the stories were mainly written in the early 1990s, so the picture they paint is of life in North Korea more than two decades ago now. There’s a broad range of characters and settings - from remote mountain huts to the capital, Pyongyang, from a high-ranking intelligence officer to the disgraced son of a traitor. They’re very much depictions of ordinary lives, of struggles and hardships but also of great, albeit quiet, acts of love.

What do we know about the state of literature – and access to foreign literature, if any - within North Korea?

I’m afraid I’m no expert on this; The Accusation itself is the sum total of my engagement with North Korean literature. It’s generally classed as socialist realism, though that’s probably about as helpful as most designations are. Barbara Demick writes that the few foreign books which are available are reserved for the elite, but that Gone With The Wind is quite popular.

As a working writer in North Korea, Bandi has been published under conditions of censorship and state control – and the breadth of literature available in the country is similarly constrained. How do these issues affect the style of Bandi’s illicit fiction writing?

Bandi’s writing has a lot of the features which translator-scholars like Stephen Epstein, Bryan Myers and Shirley Lee have identified as characteristic of North Korean fiction: epiphanic moments, purgative violence, strong female characters. I want to follow their lead and engage with North Korean writing on its own terms, not dismiss it as incapable of having any artistic value, while recognising that it’s nonsensical to assess Bandi’s work without taking his circumstances into account. His writing has an urgent, oral quality, with a frequent use of direct address, and tends towards what we would consider melodrama and sentimentality. Reading work from unfamiliar literary traditions prompts us to re-examine our ideas of what literature can and should be - that’s why I love translations. Melodrama can be 'a way of examining the social basis of certain emotions by exaggerating them' (Rachel Ingalls). It’s also by no means alien to South Korea, as anyone who has even seen their TV dramas can attest.

What, if any, are the linguistic differences between the Korean of the North and the South?

There are quite divergent dialects within both North and South Korea, so that also applies between the two countries. The South uses a lot of foreign loanwords, particularly from American English, so words like computer, elevator, ice cream are simply transliterated into hangul. In the North, they’ve tried to keep the language purer, which means thinking up inventive coinages like 'ice peach flower' for ice cream. Isn’t that lovely?

How did you get involved in translating The Accusation?

I knew the book’s agents, Barbara Zitwer and Joseph Lee, as they also represent Han Kang; they recommended me to Peter Blackstock at Grove when they sold US rights to him.

In our interview between yourself and Han Kang you talked about the discursive, conversational method the two of you developed in translating The Vegetarian. What was it like translating an author you (presumably) couldn’t communicate with?

Actually not that strange, and certainly not unusual among translators (though the author is more often dead than incognito). I definitely feel that the time I’ve been able to spend with Han Kang and Bae Suah, the two authors I mainly translate, is both a personal and a professional blessing. But for me the author’s voice and intention are all there on the page, so I never discuss a translation while I’m working on it.

And what is it like translating a culture you (presumably) can’t visit or engage with?

Again, this isn’t unknown in translation, though the impediment would usually be temporal: I’ve visited Gwangju, for example, but not Gwangju in 1980, as it appears in Han Kang’s Human Acts. What was useful was for me in the case of The Accusation was that a lot of Korean culture is shared across the border. In particular, the stories with a rural setting felt quite timeless, with environments and practices I could recognise from mid-20th century South Korean fiction.

How and why did you become a translator of Korean literature?

I was drawn to literary translation quite consciously because it seemed to combine the two things I was most passionate about, reading and writing, as well as providing the perfect excuse to finally learn a language other than English. As for which language, Korean seemed a good bet – barely anything available in English, which was exciting for me as a reader and, I hoped, would be useful professionally. I began teaching myself the language in 2010, the same year I started a Korean Studies MA at SOAS, and started translating in 2012.

You won the Man Booker International 2016 with author Han Kang for The Vegetarian. How has this affected your life and work?

It’s been simultaneously overwhelming and exhilarating. The biggest change has been being invited to so many international literary festivals and universities - I’ve visited Paris, Venice, the US, India, all for the first time, and met so many brilliant people working in translation, world literature, publishing and bookselling. I feel I have a responsibility both to make the best use I can of the platform I’ve been given and to make sure it extends to as many other translators as possible. I don’t think I’ve actually taken on any new translation contracts since the prize.

What is the state of fiction in translation in the UK at the moment, and how has that changed in recent years?

Translation is definitely having a moment. Over the last few years there’s been a sudden flourishing of small presses taking artistic risks, which is often synonymous with publishing translations. Market research shows that translation punches above its weight in terms of sales, and while the tiny percentage is nothing to shout about in itself, it does mean that only the very best gets through, making ‘translation’ a byword for originality and excellence. Now, the bigger publishers are also waking up to the fact that translation sells. Several of the biggest-name contemporary authors, the ones who can boast a cult following, are ones we read in translation: Han Kang, Elena Ferrante, Karl Ove Knausgaard.

And when we talk about translation, we also have to talk about translators. The fact that the MBI exists, in its new guise rewarding author and translator equally, is thanks to the generation before me fighting long and hard for our craft to be given the credit it deserves. It’s becoming the norm for translators to be properly credited by publishers and reviewers, given royalties and paid a slightly more than subsistence rate.

You set up the publisher Tilted Axis Press in 2015 with ‘a mission to shake up contemporary international literature’, focusing on Asian writing in translation. Can you tell us more about this project?

The aim for the press was a mixture of things: to publish cult, contemporary Asian writing, mainly by women. To publish it properly, in a way that makes it clear that this is art, not anthropology. To spotlight the importance of translation in making cultures less dully homogenous. And to improve access to the UK publishing industry, i.e. no exploitative unpaid internships.

So far, our list includes Bengali, Korean, Indonesian, Uzbek and Japanese. Next month, we publish the UK’s first ever translation of Thai fiction, which is both a) insane, b) the reason we exist. We recently relocated to Sheffield, becoming a part of the Northern Fiction Alliance - breaking publishing out of the London bubble with fellow translation heroes And Other Stories and Comma Press.

What’s next for you?

I have new translations of Han Kang and Bae Suah coming out in November ’17 and January ’18 respectively, and I aim to continue translating their work for as long as they keep writing. I’m also finding more time for teaching and mentoring - I’ll be leading the Korean group at the BCLT Summer School again this year, mentoring an emerging Korean translator through Writers Centre Norwich, and taking up a translator’s residency at the University of Iowa.